Space code of conduct: the challenges aheadby Ajey Lele

|

| Space negotiations are going to happen in a changed geopolitical atmosphere than that of the Cold War era. |

It is important to remember that there are no absolutes in the arena of arms control and disarmament related issues; it all depends on which hat one wishes to put on. Based on some recent debates, political statements, and writings on the CoC issue, it appears that two groups are emerging, with the US and EU as backers of the code and, most likely, Russia and China as the resisters. In 2008, Russia and China jointly proposed an international treaty called the “Prevention of the Placement of Weapons in Outer Space Treaty” (PPWT), which would be a legally-binding accord banning the weaponization of space. However, no major progress has been made to win support for this treaty. Under these circumstances, Russia and China would probably react to this CoC with the PPWT.

Amongst the other spacefaring nations, Japan is supporting this idea and India is yet to disclose its position. Notionally, any new idea proposed regarding space safety and security efforts needs to be welcomed, and from that viewpoint states should consider participating in the proposed CoC deliberations. In particular, other spacefaring states like Iran and Israel, and states making significant investments in space arena like Brazil, Nigeria, and South Korea, should play an important role in the process of finalizing the CoC.

On the issue of nonproliferation efforts, states like Iran and North Korea mostly have a “diverse” view from the rest of the world. It would be welcome if such states would also participate in this negotiating process. It is important to note that space is different than other “standard” arms control and disarmament approaches formulated in the 20th century. Such discussions are more about sustainability and encouraging more states to benefit from this technology than about preventing proliferation of any technology or weapon.

In the space arena there exists a possibility that debate could follow a similar pattern as happened in past, particularly in regards to nuclear, biological, and chemical weapons negotiations. Also, while some have compared the space legal regime with the “laws of sea” regime, there is a need to delink any such mindset in this regard. It is important to learn from the past experiences, but there is a need to avoid getting trapped into the similar disarmament discourses. As in the past, the self-styled disarmament advocates are expected to view the issues related to space mostly with a utopian vision, and there is a need to guard against views that are extremely idealistic in nature but do not match up with geopolitical realities.

Space negotiations are going to happen in a changed geopolitical atmosphere than that of the Cold War era. The last two decades have seen a gradual change in the geopolitical and geostrategic landscape of the world. States like China, India, and Brazil have emerged as major economic powers while the economic stability of the EU is rapidly declining. The US still has its superpower status, but with shrinking influence. All this indicates that the power balance is showing signs of realignment.

| Understanding the difficulties in reaching any globally accepted solution in the space arena, the CoC offers an alternative model as a voluntary and non-binding mechanism. |

The success of the Treaty of the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) has been viewed as cornerstone for the global nuclear non-proliferation regime. However, it is important to understand that this treaty suffers from an inherent discriminatory mechanism by which it allows five nuclear-weapon states to possess nuclear weapons, giving unfair advantage over other states. Even the most successful treaty mechanism, the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC), has witnessed non-compliance. Both the Russia and the US have failed to meet the April 29, 2012, deadline to destroy their stocks, showing disrespect to the treaty provisions. They have cited technical and financial reasons for this failure, and it may take an additional decade to fully destroy their stockpiles. Also, the pattern visible with the climate change debate indicates that there are major differences of opinions among developed and developing nations. In regards to issues related to space debris already opinions have been expressed that the “polluters” must pay.

The most obvious contrast in regards to a number of past negotiations and present space negotiations is that the grouping of P-5 nations is not expected to be on the same side of the fence. The basic problem is about the differences in regards to the issues related to missile defense among the US, Russia, and China. Also, rhetorical views have mostly been expressed by the major powers in respect of counter-space measures and space-based weapons, although their exact intentions are still unclear.

It is important for second-rung spacefaring nations, and other nations keen to develop their space capital, to view the present process of negotiations within the backdrop of above realities. Understanding the difficulties in reaching any globally accepted solution in the space arena, the CoC offers an alternative model as a voluntary and non-binding mechanism. A simplistic way to look at this proposal is that at least some beginning has been made and that should be welcomed. However, we need to have deeper debate on this issue.

The main question that many nations should ask themselves is: “Just because a few states in world have differences of opinion on outer space issues, should the rest of the world allow them alone to have their say?” Recently, a private company successfully sent a robotic craft to the International Space Station. Some organizations and governments have started making investments into the development of spaceports. These and other developments make it obvious that industry will have a major stake in the future. The past experience, particularly from the Biological Weapons Convention (BWC), indicates that in order to preserve the interests of industry, states normally shy away from getting bound by any legally binding mechanisms. In the space arena, it is also important to protect the legitimate interests of the industry; however, it is also important to have proper checks and balances in place.

| In the interest of space security and sustainability it is important to lobby for a stronger CoC that binds nations to adhere to its provisions. |

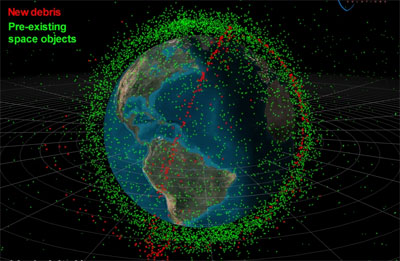

The proposed CoC is also about transparency and confidence building measures. Therefore, it is also necessary to debate on the nature of “transparency” currently being observed in the space arena. ASAT (anti-satellite) technologies have been at the center of this debate for the last five years. In January 2007, China destroyed one of its own weather satellites at an altitude of 850 kilometers, creating a significant amount of debris. The US, meanwhile, smashed its own defunct satellite at an altitude of 240 kilometers in February 2008. The Chinese test was a surprise to the rest of the world, while the US had announced its intentions beforehand. Both these tests could be viewed as opportunistic tests, when the states took the chance of converting a nonfunctional and falling satellite as a target to indirectly demonstrate their ASAT capabilities. Last month, X-37B, the mysterious US spaceplane, returned from space after 15 months in orbit. This was second such mission, and the US is not ready to disclose any of its intentions in this regard. There is also a veil of secrecy to some degree surrounding China’s ongoing efforts to develop a space station.

All this indicates that some states are not keen to discuss every activity they undertake in space. If this is what transparency is all about, then what is the use of joining a CoC that would have no control over a state’s erratic behavior in space? The CoC should expect openness and transparency in the information provided by the states in regards to their existing and future space agendas. However, the track record of another voluntary and non-binding mechanism in missile nonproliferation, The Hague Code of Conduct (HCoC), is not very encouraging. The strategic and business interests of big players in the space arena are likely to supersede their CoC commitments. For this purpose it is important to include some kind of accountability mechanisms into the CoC.

The negotiations of a space CoC scheduled for this October offers an opportunity to undertake serious negotiations on outer space issues for the first time in decades. This opportunity should not be wasted. In the interest of space security and sustainability it is important to lobby for a stronger CoC that binds nations to adhere to its provisions.